![]() In late 2014, CUSP began an investigation into the possibility of using native wood rotting mushrooms to digest wood chips, a particularly troublesome by-product of forest mitigation/restoration treatments. This study, “Fungal degradation of the woody by-products of forest management activities,” is entering its 15th year. Multiple partners have participated in the project, and dozens of volunteers have donated their time, sweat, and care to get us here.

In late 2014, CUSP began an investigation into the possibility of using native wood rotting mushrooms to digest wood chips, a particularly troublesome by-product of forest mitigation/restoration treatments. This study, “Fungal degradation of the woody by-products of forest management activities,” is entering its 15th year. Multiple partners have participated in the project, and dozens of volunteers have donated their time, sweat, and care to get us here.

As one would expect, wood-rotting mushrooms are very good at rotting wood. Millions of years of adaptation have led to their ability to break down cellulose, one of the two main components of wood, along with lignin. These are both highly resilient natural fibers that can resist decay for decades, and sometimes centuries. Over the course of this experiment we have demonstrated the reduction of piles of wood chips into a rich compost-like material that closely resembles natural humus- something that is in short supply in our surrounding woods. We sought a method of treatment that would require very little effort and basically work on its own. Each season gets us closer to that goal.

The Lab:

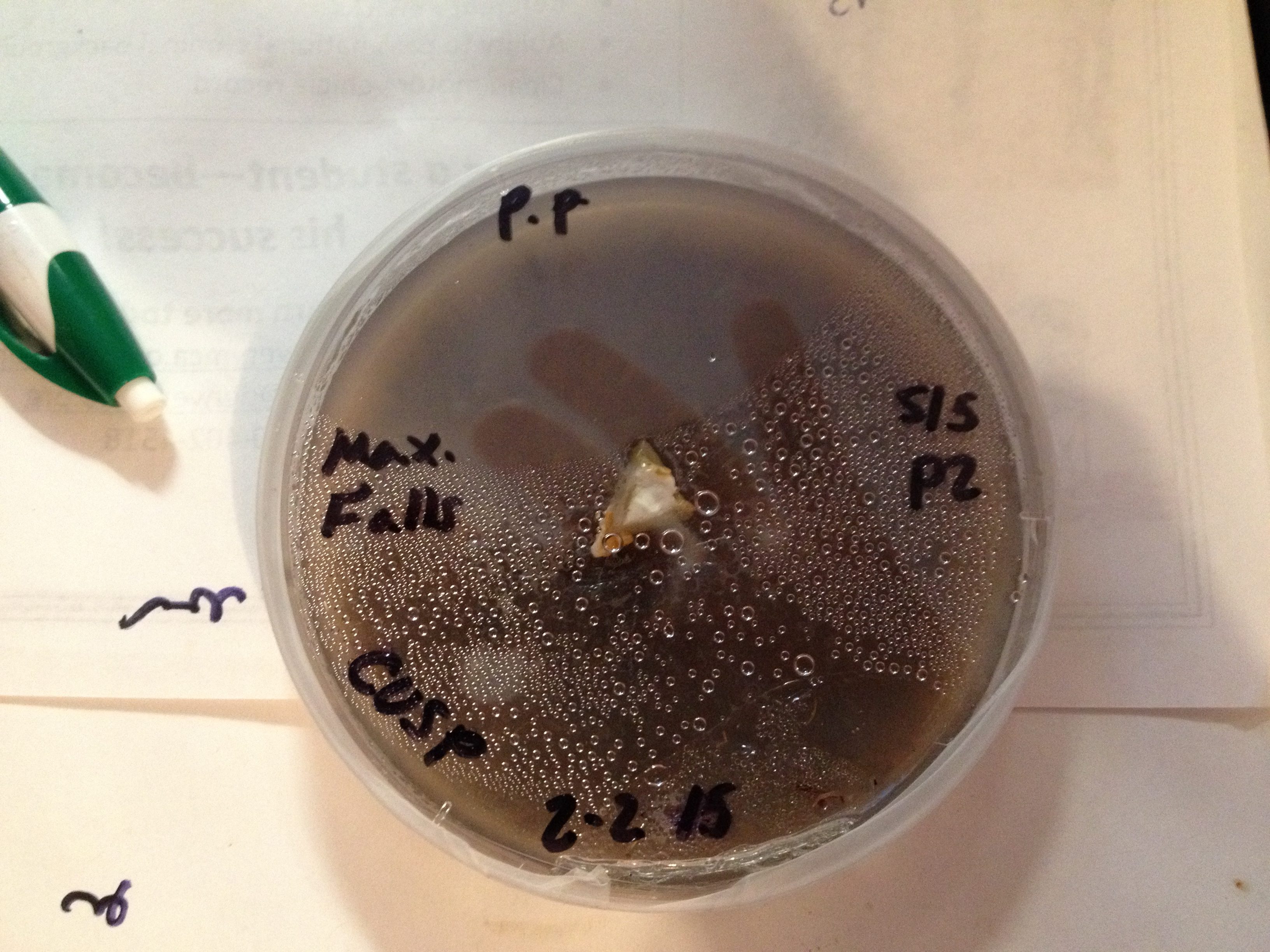

The project began by collecting native mushrooms in the wild and cultured them, similar to how mushrooms are propagated for retail markets. Under sterile conditions, living tissue is placed on agar media (PDA, wPDA*) to grow.

Once we have petri dishes of mycelia, we select the healthiest and most vigorous specimens and culture them into mason jars. Culturing into mason jars is the beginning of what we call “expansion.” Large quantities of this “spawn” are necessary to for the breakdown process in the wild. At the same time, we also begin introducing them to their desired medium- wood chips.

We use wood chips from the site we are planning to inoculate the mushrooms into so that they are perfectly prepared (trained, as we call it) to thrive and break down the wood chip beds. The spawn is expanded two more times. First, into 6-pound bags of wood chips, and those bags are used to initiate another five or so bags of wood chips each. In 2017, we produced almost 50 bags of spawn for inoculation.

Lab culturing is the most time consuming portion of the mushroom project.

|

|

|

|

The Field:

Once a sufficient amount of spawn is created, the bags of spawn are taken to the field to “inoculate,” or distribute, into the wood chips. Staff and volunteers prepare sites for inoculation using clean, but no longer sterile, techniques. The mycelial blocks that grow in the bags have sufficient mass to protect themselves from the native fungi and bacteria. The blocks are buried in the wood chips and covered. Once placed in this manner, the mushrooms thrive and need no more help from us.

|

|

|

|

Results:

The fungi have done an admirable job of consuming the wood chips and converting it to compost. The nutrient composition of the compost is very good, as Oyster mushrooms use bacteria to increase the available organic nitrogen, something that is very scarce in these ecosystems. They do this in a manner somewhat like legumes, where nitrogen-fixing bacteria grow on the mycelium, instead of the roots.

For complete information, please read the following reports.

Links to Pre-publication study:

Link to Final Chatfield Report:

Chatfield Mushroom Degradation Trial

Mushroom Degradation in the News:

Mushrooms in wildfire prevention

* PDA- Potato Dextrose Agar, wPDA- Potato Dextrose Agar with finely powdered wood dust

DONATE to the CUSP Mushroom Study